Nigeria, Africa’s top crude oil producer, has seen its output surge significantly in recent times.

The country, which currently produces about 1.6 million barrels per day (bpd), has an OPEC benchmark of 1.5 million set for it for 2025 earlier this year.

In its 2025 budget forecast, however, the West African nation targets 2.06 million barrels of crude for the year, although a considerable portion of it is expected to come from condensates.

Condensates are crude oil obtained from gas exploration, and they are not captured in OPEC’s quota calculation.

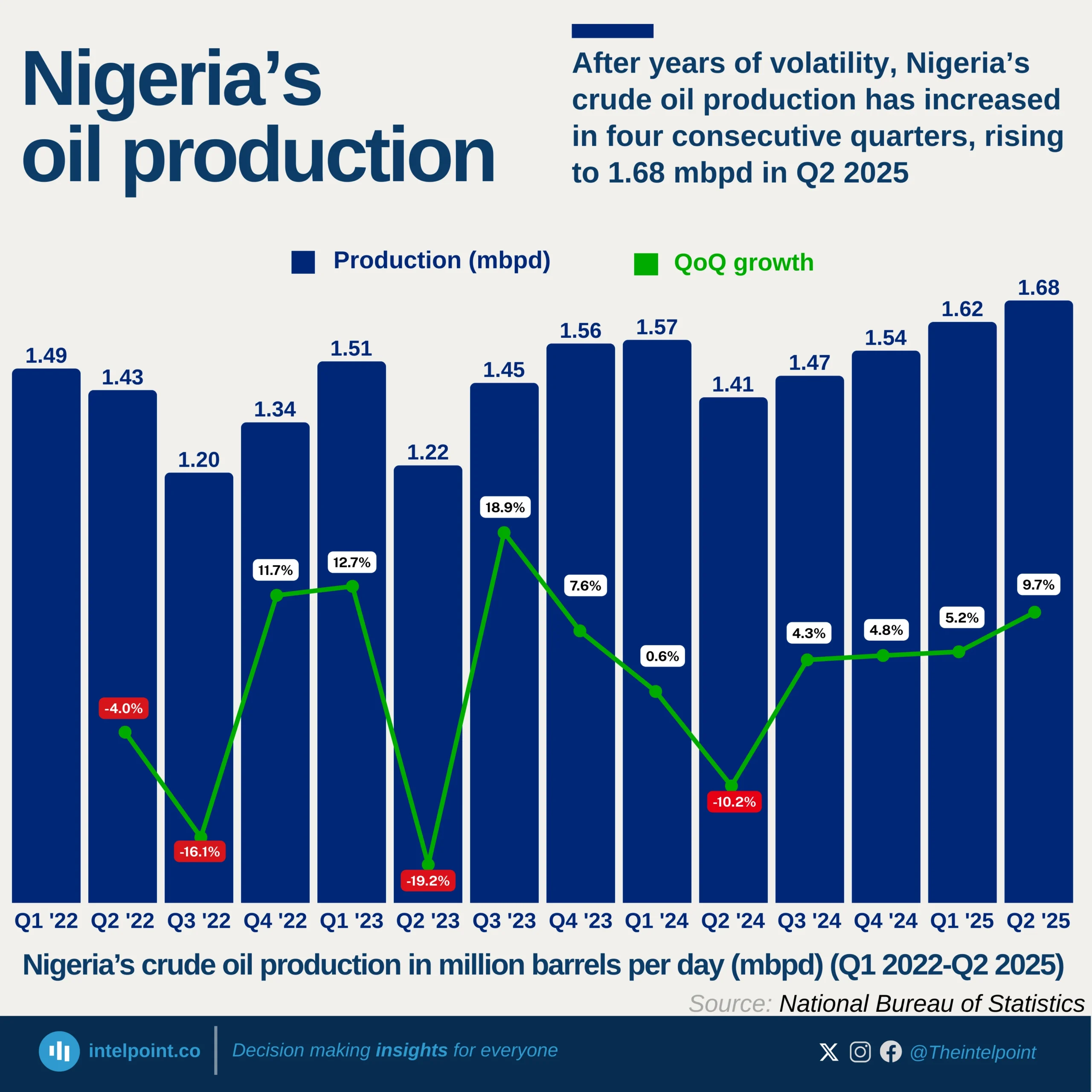

Prior to mid-2025, Nigeria had continually failed to meet its OPEC quota, producing between 1.3 million to 1.4 million bpd.

But all that has changed, with production now getting closer to its pre-COVID era when the country was producing around 1.7 million bpd.

Oil is the lifeblood of Nigeria’s economy, representing over 80% of its real foreign exchange inflow into the country.

A continual appreciation in oil production therefore determines the country’s economic stability, particularly the strength of its currency.

However, as a member of the Saudi-led cartel, Nigeria has the moral and political obligation to adhere to its supply quota or it might end up facing sanctions from the body.

OPEC+ regulates its members’ production benchmarks to avoid supply gluts or to compensate members who intentionally cut production to help stabilise global crude oil prices.

In recent times, the body has allowed some members, like Kazakhstan and the UAE, to increase their supply to meet growing crude demands.

The group, which introduced a hefty 2.2 million bpd crude oil cut in November 2023 to help stabilize the oil market, has since reversed some of these restrictions.

Between April 2025 and September, OPEC+ allowed members who adhered to earlier cuts to produce around 1.65 million bpd more in the global market, although this remains below the initial cut imposed in 2023.

The Saudi-led group has maintained that any hike in supply must be mitigated with falling crude prices to avoid a price shockwave in the market.

Of all the increases, however, Nigeria was not allocated a higher production benchmark.

In July, during OPEC’s global seminar, the head of Nigeria’s oil firm, Bashir Ojulari, said the country shares the broader interest and optimism of the body to further produce more oil.

Ojulari, who also commented on the increasingly favourable oil production outlook in Nigeria, said the demand for more crude as campaigned by OPEC indicates a need to bridge the gap created by the shortfall of green and renewable energy.

“It’s also important to note that in recent years, the push for energy transition caused delays in many projects and investments. Now, those investments are returning because it’s becoming clear that the world needs a balance in energy supply.

“Progress in renewables has been slower than expected, while energy demand remains strong. That gap is fueling the current recovery, in my view,” Ojulari said.

He further added that the country is targeting a production volume of 3 million bpd in the next two years, suggesting a lobby for increased crude production.

The post-Covid rebound

Prior to the global economic shock of 2019 and 2020 as a result of Covid-19, Nigeria’s crude oil production benchmark by OPEC was around 1.73 million bpd.

However, this was reversed to 1.38 million in 2023 as the country was unable to pump more oil.

Beyond the role of Covid, Nigeria’s crude output continued to falter significantly between 2020 and 2023 due to low investment in its offshore environment as well as pipeline vandalism and oil theft.

At some point, there were reports that the country was losing over 400,000 barrels of crude per day.

This led to a historic decline in production, with the country losing its top spot to another oil-rich nation, Libya.

But the trend was quickly reversed in 2024, with a huge crackdown on oil theft from efforts by the state-owned oil firm as well as community policing.

A recent report shows that oil theft in the country has fallen to a 15-year low — a meagre 9,000 bpd.

Investment has also rebounded to pre-Covid levels, with Nigeria attracting over $8 billion in its upstream sector.

A huge chunk of that pledge would come from Shell Plc, which has decided to invest about $5 billion in the country’s Bonga North offshore field.

With positive investment outlook and a reduction in theft, Nigeria has been able to increase its production to an appreciable growth of over 1.6 million bpd.

According to the latest OPEC report, Nigeria produced 1.54 million bpd in August, edging above its allocated quota of 1.5 million.

Local authorities, however, put the country’s production at about 1.6 million bpd, apparently counting condensate output in the volume.

The increase in output as well as investment opportunities implies that Nigeria may be seeking a new OPEC benchmark — possibly 2 million bpd — in the next OPEC meeting.

Nigeria’s oil quota is expected to last till the end of December 2026.

But the country’s local economy may not wait that long.

Petrodollars still account for most of its revenues, and an increase in oil royalties could only come from a surge in production.

The OPEC+ dilemma

The big question is whether Nigeria can sacrifice a higher oil production prospect for fulfilling its obligations to OPEC+.

In recent times, some have advised the West African nation to ditch the Saudi-led cartel and align more with the West, particularly the United States, in selling to the global market.

But such a move is easier said than done. Nigeria is one of the oldest members of OPEC — and its oldest African member — joining the group in the early 1970s.

While leaving OPEC may not be an option, lobbying for a higher output may be an easier alternative.

Unlike most countries in the OPEC+ family, Nigeria was not among the nations that earlier cut production, and it’s reasonable that it was not allowed to produce more.

At a time when OPEC members were cutting quotas, Nigeria had no output to cut since it wasn’t even producing enough to meet its own local demand.

Now that the tide has turned, it may be difficult for the cartel to justify compensating the country with a higher output.

Then there’s the politics of keeping oil prices within a reasonable range — mainly around $60 per barrel — to allow profit margins for new exploration and investment.

The Trump effect hasn’t helped either. With incessant pressure from Washington for a reduction in oil prices, a higher output would mean prices fall below profitable margins.

“OPEC+ seems to be gradually shifting from purely defending prices to reclaiming market share, given that prolonged cuts have allowed non-OPEC producers to expand their influence,” oil and gas expert, Benjamin Ajayi, observed.

Recently, OPEC+ opted for a modest 137,000 bpd crude oil increase as fear of a supply glut influenced the decision.

The cartel has already unwound about 2.7 million bpd of cuts by its members this year alone, seeing the price of crude move from a peak of $80 to about $65 per barrel.

The geopolitics for Nigeria would mean choosing between a lower oil price with higher output or maintaining a modest quota for a better price return.

On net, the country will have to decide which makes more sense.

From a political angle, producing 2 million bpd looks good for government optics. After all, the government could easily argue that it has no influence over oil prices.

And indeed, it doesn’t — which means if oil prices finally fall dramatically (and there are myriad predictions they will), Nigeria’s only lifeline would be to produce more.

At $60 or less, it would take a 2 million bpd output for the West African nation to break even and maintain a reasonably healthy economy.

When oil prices plummeted heavily during Covid, Nigeria’s economy went into recession. At that time, production was also low. Perhaps a higher production could have saved the economy.

Refining capacity and the Dangote factor

To add to it, the country has also increased its local refining capacity.

With a 650,000 bpd petrochemical plant seated on its shore, much more production would mean more allocation locally.

While selling locally may not necessarily mean inflow in greenbacks, it saves the nation’s bottom line.

The Dangote refinery has been hailed as a game changer. If it refines local crude, it can boost the nation’s dwindling economy and save its import bills significantly.

So far, it’s doing just that. The refinery has driven fuel imports to an eight-year low in the West African country. It has also helped Nigeria lose its long-held status as the biggest importer of petroleum products — a title now claimed by South Africa.

The more oil drilled from the ground, the more allocation Dangote gets.

Perhaps Nigeria does not need to wait till its December 2026 timeline runs out to ask for more quota.

Its argument could be that a large portion of what’s produced would be sold locally, especially now that it has a surge in refining capacity.

It all boils down to playing its politics right at the OPEC+ table as Africa’s largest oil producer there.

The bigger picture

Producing oil goes beyond politics. Investment, more drilling, more block allocations, revival of old wells, and exploration of new ones all come into play.

So far, Nigeria has attracted huge investment in its oil and gas sector.

But most of these have come as pledges and not necessarily real cash in hand — like in the case of ExxonMobil and its offshore assets in Nigeria.

The real money is yet to show. And perhaps it’s because most IOCs are not in the best financial shape given dwindling oil prices and a number of troubled assets across the continent, many of which are yet to turn profit.

Nigeria needs to show its cards early enough. OPEC+ for now is in a happy place when it comes to supply. But that pendulum won’t swing in that direction for long.

The geopolitics may change soon, and the oil market may become so supplied that it beats forecasted demand.

If the West African nation wants more quota, perhaps it’s time for it to ask. If not, that option may not be on the table any longer.