In October 2025, Daniel Chapo, Mozambique’s newly elected president, visited the United States and met with its Vice President J.D. Vance. He also met with top oil officials at American oil major, ExxonMobil’s headquarters. Chapo’s visit was a historic one. The well suited liberal president became the leader of the southeastern African country earlier this year.

Chapo seems to be consolidating on emphasis on gas that marked the tenure of the last president, Filipe Nyusi.

Nyusi’s presidency, however, was faced with heightened economic pressure and rising insecurity that left many oil companies to abandon their facilities.

Since resuming office, the new president has tried to keep insecurity at bay, particularly in Cabo Delgado.

Perhaps his hard work is showing early signs. Oil majors are returning to the country, and investment seems to be on the rise again.

Mozambique, a country hosting over 35 million people with a burgeoning youth population, has now become a hotspot for oil and gas majors, including TotalEnergies, ExxonMobil, and Eni. The country might become the biggest exporter of LNG by the end of the decade, with many projects spread across the northern provinces and other parts.

Chapo’s visit to ExxonMobil’s headquarters was aimed at reviving the conversation around the $30 billion LNG project being considered by the American oil company.

Around the same time, the French oil major TotalEnergies recently announced that it has lifted its force majeure on its $20 billion LNG project in Mozambique.

Chapo’s political timing also makes sense, aligning with global interests.

Trump was instrumental in the approval of a $5 billion LNG loan for the project itself.

Mozambique’s security crisis dwindles

Mozambique was plagued by insecurity between 2019 and 2020, particularly in the northern part of the country where many gas facilities are located.

TotalEnergies was forced to halt its $20 billion LNG project and evacuate employees following attacks by terrorists and non-state actors.

The site remained shut for four years until the new administration, working with the French oil major, restarted the project. Insecurity still remains a challenge, but it has been reducing. Oil companies are taking note. Italian energy company Eni, for instance, has moved in and greenlighted a Floating Liquefied Natural Gas (FLNG) deal worth $7.2 billion in Rovuma Basin.

Given the level of investment, the scale of projects, and Mozambique’s growing role in energy development, one might argue that the country is Africa’s gas nation of the year 2025. And such assumption won’t be far from reality.

Gas, a transitional fuel in Africa

Moreover, Gas is rapidly becoming the fuel of the future for many African countries. It is seen as a cleaner transitional fossil fuel compared to crude oil or coal. Countries such as Nigeria, Egypt, Congo, and Tanzania are all embracing gas as a way to reduce carbon emissions while industrializing their economies.

Mozambique is a huge part of that conversation.

Its geography plays a big role. With its proximity to the Indian Ocean coastal plain, Mozambique is naturally positioned for LNG exports. It is also a frontier market, unlike more mature producers such as Nigeria or Angola, with fewer legacy constraints. In addition, Mozambique is a highly integrated regional market close to South Africa, Zambia, and Tanzania. Many oil majors see these opportunities and are willing to place a bet on it.

The country also has the resources to match the ambition. It holds about 180 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, making it one of the largest gas reserve holders on the continent. Offshore projects in the Rovuma Basin, particularly Area 1, rank among the biggest gas discoveries Africa has seen. When completed, these projects are expected to supply global markets, especially in Asia and Europe.

No discussion around gas production, LNG exports, or gas-led industrialization in Africa feels complete without mentioning Mozambique.

Setbacks, ambitions and other projects

Still, setbacks remain. Insecurity is still high in certain parts of the country, forcing companies to evacuate staff from time to time. Financing has also become an issue.

Recently, a UK court ruled that a $1.2 billion pledge be withdrawn from TotalEnergies’ $20 billion LNG financing package. In addition, a German party pulled a $2.3 billion commitment. Total’s CEO, Patrick Pouyanne, has said the firm may need to raise additional funding to close the gap left by these other financiers.

Project costs have also risen after years of abandonment and force majeure, with some reports estimating an additional $4.5 billion needed to complete the project. All of this could affect timelines and financing structures.

Even so, gas production and exports remain a major hotspot for Mozambique. Earlier this month, South Africa’s president, Cyril Ramaphosa, visited the site of a newly completed LPG facility in the country.

Ramaphosa was there to commission Mozambique’s first domestic production of LPG plant. The facility is expected to reduce imports from neighboring countries, as well as Europe and Asia.

Other nations’ gas ambition

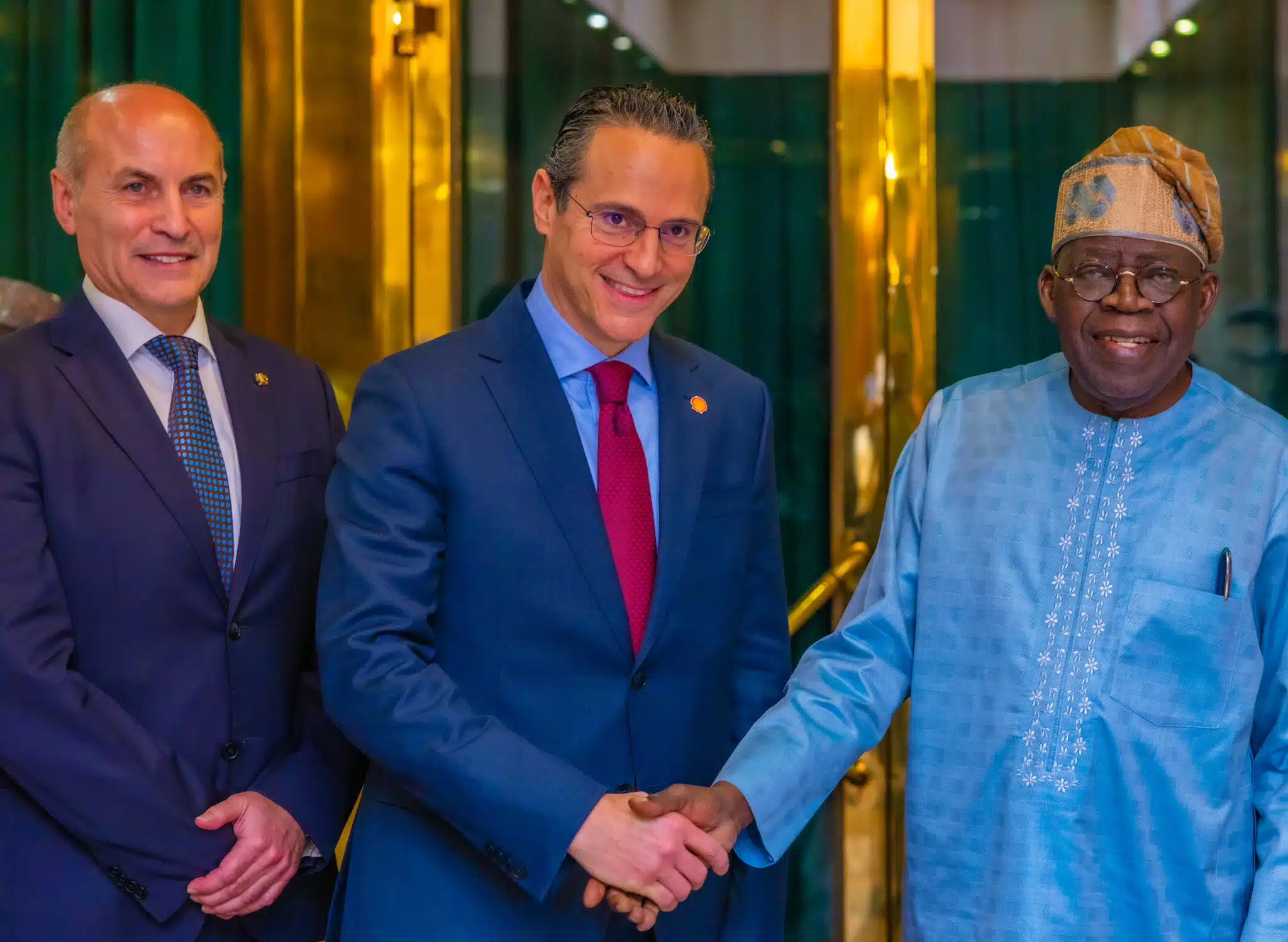

Of course, Mozambique is not alone in seeing gas as a transition fuel of the future. Nigeria, for example, launched its Decade of Gas in 2021 and is working to move away from gas flaring and over dependence on exports toward greater domestic utilization. Recently, Shell PLC signed an agreement with Sunlink to explore what is being described as the first non acidic mega gas project in the country, valued at over $2 billion.

Similar stories are unfolding in Congo, Tanzania, Egypt, and Angola. Meanwhile, Egypt’s experience has been more complex. In 2024, one of Africa’s biggest LNG exporters reversed course and became one of the largest importers of the same commodity after low production from its key Zohr field. Still, Egypt has begun to adjust. Production has improved lately. The country said it will invest over $8 billion in gas projects in the next five years.

Yet Mozambique continues to stand out. It appears to be attracting the bulk of foreign direct investment into gas facilities and megaprojects on the continent. Total is leading much of that push, expanding its footprint across less mature basins in countries such as Congo, Uganda, Namibia, and South Africa. The French oil major is also developing a $5 billion pipeline in Uganda to transport oil and gas to Tanzania.

How Mozambique stands out

In Mozambique itself, however, the scale is unmatched. The $20 billion LNG project remains the single biggest foreign investment on the continent. It olny rivals Nigeria’s $20 billion Dangote Refinery in size and ambition. According to comments from its CEO, the operator remains committed to completing the project by 2029.

If all goes as planned, Total, Exxon and Eni — some of the biggest names in oil and gas — would all have billion of dollar facilities in the southeastern country in a few years.

Mozambique’s gas would be exported through the oceans to Europe, America and the Middle East to build infrastructure, power energy, boost agriculture and sustain aviation.

The country is reportedly training over 100 engineers to fill in the gap for local skill acquisition for these forthcoming projects.

No doubt in 2025, Africa as a continent attracted notable investment in gas. In fact, Nigeria debut its first 50 block gas blocks bid in its latest licensing rounds. But when it comes to the country on every oil and gas firm lips, Mozambique still seems to stand out. Perhaps it might even be Africa’s gas nation of the year, if there’s such a recognition.