When President Bola Tinubu announced on May 29, 2023, that “fuel subsidy is gone,” the ripple effects were immediate.

Fuel queues returned, prices surged from N185 to over N500 per litre, and Nigerians faced one of the steepest inflationary periods in recent memory.

But buried beneath the daily anguish and macroeconomic shocks was a remarkable shift—a dramatic collapse in reported petrol consumption.

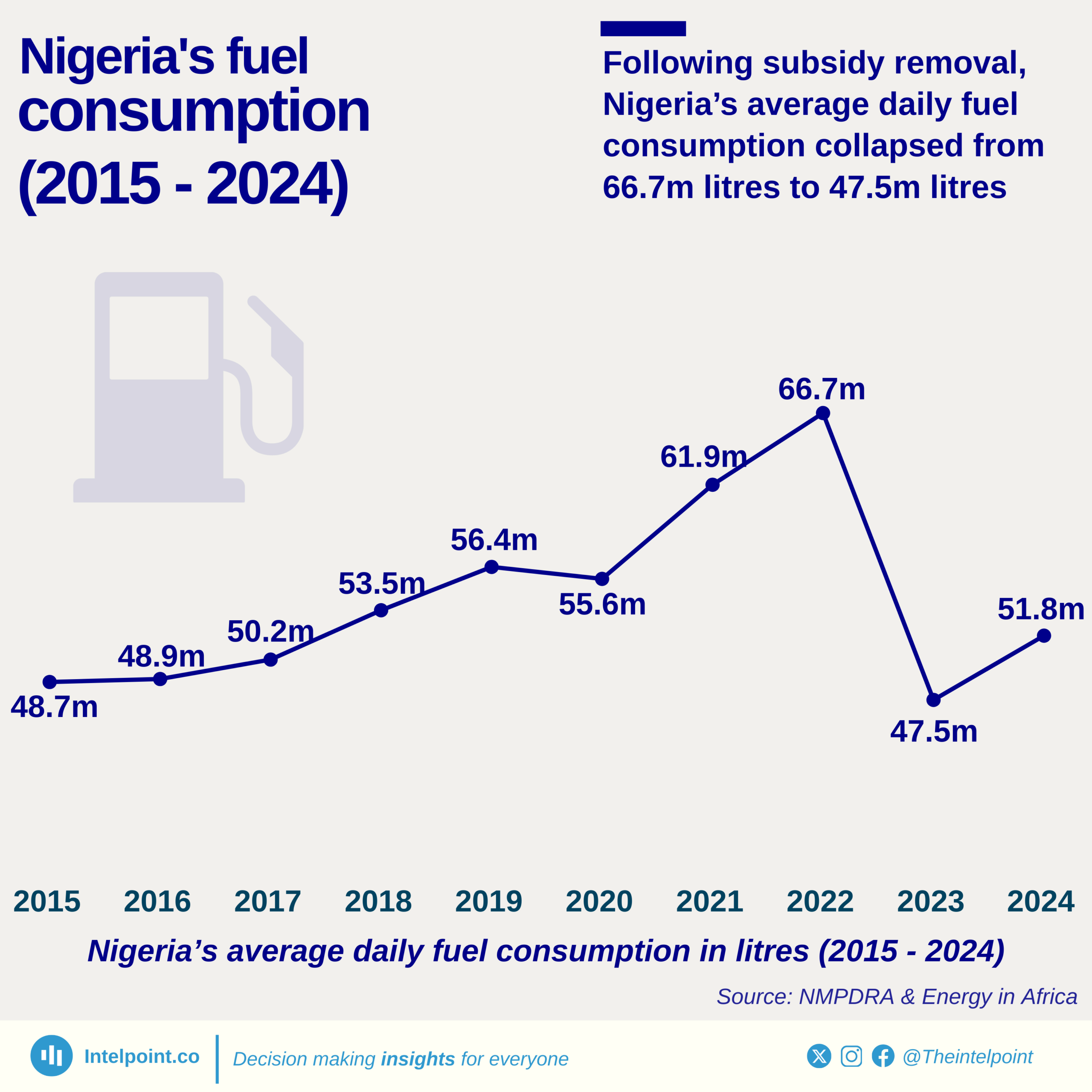

From an average of 66.9 million litres per day in the first five months of 2023, Nigeria’s fuel usage nosedived to 47.5 million litres per day in the second half of the year, according to the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA).

The trend continued into 2024, with average daily consumption hovering between 49.8 and 51.8 million litres.

The sharp drop has raised a provocative question: Were Nigerians ever consuming that much petrol, or was the subsidy regime fuelling a shadow economy of cross-border smuggling and inflated claims?

The decade in data

The NMDPRA data reveals an interesting trend as shown in the table below:

| Year/Period | Average Daily Consumption (Litres) |

|---|---|

| 2015 | 48.7 million |

| 2016 | 48.9 million |

| 2017 | 50.2 million |

| 2018 | 53.5 million |

| 2019 | 56.4 million |

| 2020 | 55.6 million |

| 2021 | 61.9 million |

| 2022 | 66.7 million |

| Jan–May 2023 | 66.9 million |

| Post-subsidy (Jun–Dec 2023) | 47.5 million |

| Jan–Aug 2024 | 51.8 million |

| Sept 2024–Date | 49.8 million |

Over the past decade, petrol consumption trends in Nigeria have mirrored not just energy demand but also deep-seated distortions in the country’s economic structure.

Between 2015 and 2022, official daily consumption figures steadily climbed from 48.7 million litres to 66.7 million litres — a 37 percent rise that outpaced both population growth and vehicle registration rates.

This steady climb was rarely questioned, often treated as evidence of rising economic activity.

Yet, with no corresponding industrial boom, no mass expansion in private car ownership, and consistent reports of widespread smuggling, these figures increasingly pointed to an underlying consumption bubble.

The collapse of reported consumption following the 2023 subsidy removal — a sharp drop of nearly 20 million litres per day — offers a retrospective correction.

It exposes how, for years, Nigeria’s fuel economy operated within a framework of artificial demand, propped up by policy-induced market distortions rather than genuine domestic need.

In essence, the decade’s consumption data was less a mirror of national growth and more a magnifying glass over a subsidy-driven shadow economy.

How Nigeria built a distorted fuel economy

Nigeria’s journey into a distorted fuel economy was not the product of a single misstep but rather the accumulation of decades of well-intentioned, yet ultimately unsustainable, policy decisions.

What began as a measure to shield citizens from the volatility of global oil prices in the late 1970s steadily evolved into one of the most entrenched and expensive subsidy regimes in the world.

By the early 2010s, the full cost of maintaining this system became impossible to ignore. In 2011 alone, fuel subsidy payments ballooned to N2.6 trillion — a figure so large it rivalled the entire federal budget for critical sectors like health and education.

When former President Goodluck Jonathan attempted to dismantle the regime in January 2012, it provoked mass outrage, culminating in the Occupy Nigeria protests that paralysed the country for days.

For many Nigerians, cheap petrol had become less an economic policy and more a perceived entitlement, deeply woven into the national psyche.

Beneath this public attachment, however, lay a system riddled with structural flaws. Nigeria’s downstream petroleum sector was mired in opacity, where subsidy claims were often based on self-reported imports, with limited independent verification.

The 2012 House of Representatives probe into subsidy payments exposed just how dysfunctional the system had become: billions of naira were fraudulently paid out to companies that never supplied any petrol.

In one striking case, a firm received N1.9 billion without owning a single vessel or delivering a drop of fuel.

These revelations pointed to a deeper rot — the subsidy mechanism had morphed from a social safety net into a sophisticated network of rent-seeking, dominated by politically connected businesses who profited handsomely from phantom transactions.

Attempts at reform invariably met fierce resistance, not just from the street but also from elite beneficiaries determined to protect their lucrative interests.

Under President Muhammadu Buhari, elected in 2015 with promises of reform, there were sporadic attempts to address the subsidy burden.

A partial deregulation was introduced in 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic, taking advantage of the global crash in oil prices to push through fuel price adjustments.

Yet, as oil prices recovered in 2021, the subsidy quietly re-emerged — and with it, petrol consumption figures once again surged.

At its core, Nigeria’s subsidy dilemma embodied a paradox: the state was simultaneously spending trillions of naira to sustain artificially low fuel prices at home while undermining its ability to invest in the very public services that could improve citizens’ welfare in the long term.

Roads, schools, hospitals, and power infrastructure languished, even as resources were siphoned off into an increasingly inefficient and leak-prone energy ecosystem.

The political economy of fuel subsidy thus became self-reinforcing. Citizens, conditioned by years of artificially cheap petrol, grew hostile to any attempts at reform, even when the long-term benefits were clear.

Wary of public backlash and conscious of the entrenched interests that funded their political survival, politicians largely kicked the can down the road.

It took a combination of fiscal crisis, dwindling oil revenues, and external economic shocks to force the reckoning that had been avoided for decades.

Yet even now, the scars of the old system remain visible — in the country’s battered public finances, in its fragile energy infrastructure, and in the lingering public scepticism towards government reforms.

Nigeria’s distorted fuel economy was not merely a product of policy failure; it was a mirror of broader governance challenges — an enduring lesson in how short-term populism can undermine long-term national prosperity.

Subsidy, smuggling, and shadow demand

The sharp rise in consumption between 2020 and 2022—from 55.6 to 66.7 million litres per day—defied economic logic.

“At no point did our population or vehicle base grow enough to justify that kind of spike,” said a senior downstream operator who requested anonymity.

“What we had was a lucrative arbitrage system. Buy cheap petrol in Nigeria, smuggle it across the border, and make a killing.”

Indeed, with petrol selling for as low as N185 per litre in Nigeria but over N700 in Chad, Benin, or Niger Republic, smuggling became a multi-billion-naira enterprise.

In 2022, Mele Kyari, Group CEO of the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) Limited, admitted publicly that Nigeria was losing an estimated 200,000 barrels of crude daily to theft—and a significant portion of refined products was not staying in the country.

“Most of the products we import and claim to consume domestically are finding their way out. This is not sustainable,” Kyari said.

Realignment of Nigeria’s fuel economy

When President Bola Tinubu announced the removal of Nigeria’s decades-old fuel subsidy on his inauguration day, it was a bold political gamble—one that few had fully anticipated.

While the move was risky, it was not without historical precedent.

Eleven years earlier, in January 2012, a similar attempt by Jonathan had triggered mass protests, paralysed economic activity, and nearly brought down the government.

Yet in 2023, the context had shifted dramatically. Years of chronic fuel scarcity, public exhaustion with subsidy-related corruption, and a looming fiscal crisis created conditions where resistance to subsidy removal was surprisingly muted.

Rather than erupt into mass street protests, as in 2012, the public reaction was largely resigned, driven by a widespread recognition that the subsidy had become economically unsustainable.

The immediate effects of Tinubu’s decision were sweeping. Reported petrol consumption fell sharply, dropping by over 19 million litres per day within the first month.

With petrol no longer artificially cheap, the incentive to smuggle fuel across Nigeria’s porous borders collapsed, leading to a more accurate reflection of true domestic demand.

Consequently, petrol imports declined significantly, easing persistent pressure on the country’s strained foreign exchange reserves.

Another structural shift followed: the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPCL), which had long monopolised petrol imports under the subsidy regime, began to step back, allowing private sector players to gradually enter a deregulated market.

For the first time in decades, pricing in the downstream sector was being shaped—at least partially—by market forces rather than government decree.

Yet while the macroeconomic realignment was evident, the social and human costs of the transition quickly surfaced.

The sharp rise in pump prices, reaching over ₦500 per litre in some areas, cascaded into transport and food costs, driving inflation to new heights.

By March 2025, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reported food inflation at over 21.7 percent, with transport emerging as one of the major contributing factors.

For many Nigerians, particularly those in the informal sector and rural communities, the deregulation translated into immediate hardship without a visible safety net to cushion the blow.

As 2024 unfolded, Nigeria appeared to settle into a new equilibrium. Daily petrol consumption stabilised around 50 million litres—approximately 25 percent lower than the inflated figures recorded during the subsidy era.

This “new normal” reflected not only the collapse of cross-border smuggling but also behavioural changes among citizens.

Faced with elevated costs, more Nigerians turned to public transportation, carpooling, and shorter, more essential travel.

Although the government’s efforts to promote Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) adoption gained momentum through initiatives like the Presidential CNG Initiative, uptake remained modest, limited by infrastructure gaps and public scepticism.

Nevertheless, the broader signals are unmistakable: Nigeria’s fuel market is undergoing its most profound structural shift in decades.

Yet, the ultimate success of Tinubu’s gamble will not be judged solely by the removal of the subsidy.

It will depend on whether the fiscal savings generated are transparently deployed to rebuild critical infrastructure, strengthen social protection systems, and invest in the kind of long-term economic transformation that subsidy payments had, for years, starved of resources.

Without tangible improvements in citizens’ lives, the political risk of backlash remains alive.

Removing the subsidy corrected a major market distortion—but it also exposed government performance to sharper scrutiny.

In the post-subsidy era, the public’s expectations are not just about cheaper petrol; they are about a better Nigeria. Whether this gamble pays off, therefore, rests not only on market forces but on governance outcomes.

In numbers we trust

For years, Nigeria’s reported petrol consumption was treated as gospel by budget planners and marketers alike.

But the post-subsidy crash in daily usage has pulled back the curtain on a broken system.

The numbers are now sobering—and possibly more truthful. What remains is for the government to consolidate these gains by: Deepening transparency in pricing, expanding fuel alternatives like CNG, and ensuring that savings from subsidy removal are felt tangibly by citizens.

As Nigeria navigates the aftermath of its most consequential economic reform in decades, one truth stands out: you can’t fix what you don’t measure truthfully—and finally, the country may just be doing that.