When the news broke in 2022 that TotalEnergies and Shell had struck significant offshore oil discoveries in Namibia’s Orange Basin, the reaction was electric.

Commentators rushed to dub the southern African country the “next Guyana”, recalling how ExxonMobil’s giant discoveries had catapulted the South American nation into one of the fastest-growing economies in the world.

Investment bankers flew into Windhoek, oil executives talked up prospects, and government officials painted a picture of billions in future revenues.

Two years later, that initial wave of excitement has cooled.

While Guyana’s oil story moved swiftly from discovery to development, Namibia’s appears to be stuck in a slower lane.

Shell has already taken a $400 million write-down after struggling to prove commercial viability, while TotalEnergies is being deliberately cautious in announcing development plans.

The government, eager for a breakthrough, finds itself trying to keep momentum alive in the face of Big Oil’s hesitation.

The comparison with Guyana now feels premature.

What was once seen as Namibia’s ticket to rapid transformation is increasingly a reminder of how difficult it is to replicate Guyana’s remarkable success.

The situation is not yet a crisis, but for policymakers banking on an oil windfall, the delays are worrisome.

Namibia’s oil promise and the Guyana comparison

Namibia’s oil story began long before 2022, but it was the back-to-back discoveries in the Orange Basin that ignited real global interest.

TotalEnergies’ Venus-1 well and Shell’s Graff-1 well both revealed large hydrocarbon systems, with early estimates suggesting billions of barrels of recoverable reserves.

QatarEnergy joined the partnerships, adding credibility and financial muscle.

The geology was tantalising.

Industry analysts highlighted similarities to Guyana’s Stabroek block, where ExxonMobil and its partners have discovered more than 11 billion barrels since 2015.

Guyana’s story was one of the fastest resource-to-production timelines in modern oil history, and it offered a model many hoped Namibia could replicate.

Guyana’s rise is instructive.

After Exxon’s breakthrough, the country quickly attracted billions in foreign investment. Its GDP has grown at double-digit rates for several years, driven almost entirely by oil.

By 2023, Guyana was producing more than 400,000 barrels per day, and projections suggest output could surpass 1 million barrels per day by the end of this decade.

The country, once among the poorest in South America, is now one of the richest per capita in the region.

For Namibia, the hope was obvious. The government projected that oil could transform its economy, which remains heavily dependent on mining and agriculture.

At one point, analysts speculated the country could join the ranks of Africa’s top oil producers within a decade.

The comparisons to Guyana created sky-high expectations at home and abroad.

But there are crucial differences.

Guyana benefited from relatively shallow offshore fields with high-quality crude that could be developed at competitive costs.

It also had ExxonMobil, a supermajor with a track record of moving quickly once commercial viability was established.

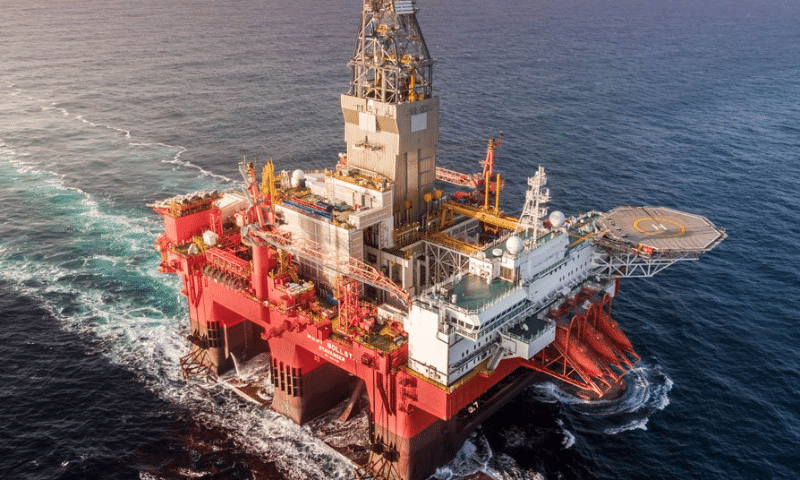

Namibia’s discoveries, by contrast, lie in ultra-deep waters more than 3,000 metres below sea level, making them technically challenging and expensive to develop.

The hesitation of oil majors

The early rhetoric from the oil companies was promising, but by 2024, a more cautious tone had set in.

Shell, after several appraisal wells, announced a $400 million write-down on its Namibian assets.

The company explained it had not yet confirmed commercial volumes that would justify large-scale development.

Its chief executive, Wael Sawan, added that while Namibia remained “an interesting play”, it was not a priority for near-term investment.

Instead, Shell highlighted regions like the Gulf of Mexico, Malaysia, and Oman, where it already had infrastructure and proven reserves.

TotalEnergies has also been measured in its language.

While its Venus discovery is regarded as the most promising in Namibia, the French major has stressed the need for thorough testing and phased evaluation.

Unlike Exxon in Guyana, which moved aggressively after its first discoveries, Total has emphasised patience, citing the technical complexity of ultra-deep offshore development.

This caution is not unique to Namibia.

Globally, Big Oil has become more selective.

According to a Bloomberg report, exploration budgets have been shrinking as companies prioritise shareholder returns, debt reduction, and the transition to cleaner energy.

The result is that frontier plays like Namibia struggle to compete with established regions where infrastructure and supply chains already exist.

The hesitation reflects a deeper shift in corporate strategy. Oil majors are under pressure from investors to avoid costly mistakes, particularly as climate commitments loom.

New projects must not only promise large volumes but also deliver competitive returns in a shorter time frame.

Namibia, for all its promise, has yet to meet those conditions.

Risks beneath the optimism

Beneath the surface enthusiasm, Namibia faces structural challenges that complicate its oil dream.

One is cost. Developing ultra-deepwater fields requires billions in upfront investment, and in a world of tighter capital discipline, that is a tough sell.

Without established pipelines, terminals, and support infrastructure, Namibia starts from a blank slate.

Guyana, by contrast, had access to nearby Trinidad’s oil services industry and could build from a stronger base.

There are also fiscal and regulatory questions.

The Namibian government has promised attractive terms to lure investors, but it is also under pressure domestically to secure a fair share of revenues and promote local content.

Striking the right balance is delicate.

Too much pressure on oil companies could slow investment further, but too little could fuel political backlash.

Already, debates have emerged about how revenues should be managed to avoid the “resource curse” that has plagued other African producers.

Environmental and global market dynamics add further uncertainty.

With the International Energy Agency forecasting that global oil demand could peak before 2030, investors are cautious about committing to projects that may not pay back quickly.

Namibia, unlike Guyana in 2015, faces an energy landscape where the future of oil is more contested.

There is also the question of timing.

While Guyana moved from first discovery to production in just over five years, Namibia’s development timeline looks far longer.

Industry experts told Reuters that first oil may not flow until the early 2030s if approvals and investments proceed smoothly.

That lag means Namibia risks missing the window when oil demand and prices remain robust.

What this means for Namibia and Africa’s energy future

For Namibia, the stakes are high.

The government has touted oil as a potential game-changer, capable of generating billions in revenues and lifting thousands out of poverty.

But the current pace suggests the transformation will not be immediate. Without firm investment decisions from Shell and TotalEnergies, the promise remains largely on paper.

This uncertainty carries lessons for the rest of Africa.

Countries from Senegal to Mozambique have also been hailed as the next big frontiers, but progress has been uneven.

Mozambique’s giant gas projects, for example, have been delayed by security concerns and market shifts.

Senegal’s Sangomar oil field is moving forward, but at a slower pace than first envisioned.

Namibia’s cautionary tale shows how difficult it is for new entrants to replicate Guyana’s meteoric rise.

Still, Namibia is not without options. The government can focus on creating a clear and transparent regulatory framework that gives investors confidence.

Lessons from Guyana suggest that speed and certainty matter.

Exxon’s success there was not just about geology but also about quick approvals and fiscal stability that reassured investors.

Namibia can also leverage its position in the energy transition. With abundant solar and wind potential, it is already positioning itself as a hub for green hydrogen.

A balanced strategy that integrates hydrocarbons with renewables could make the country more resilient in the long run.

For Africa more broadly, the message is sobering.

Big Oil’s caution in Namibia reflects a global trend where frontier markets face higher scrutiny.

While oil and gas will remain part of the energy mix for decades, the easy flow of capital into new discoveries is no longer guaranteed.

Policymakers must therefore plan for a future where hydrocarbons alone cannot sustain development ambitions.

Namibia is not Guyana

Namibia’s oil discoveries were hailed as the beginning of a new era, a chance to join Guyana as one of the great resource success stories of the 21st century.

But two years on, the contrast is stark.

Guyana is producing and reaping windfall revenues, while Namibia is still waiting for its moment.

The geology is promising, but the hesitation of oil majors, combined with high costs, regulatory questions, and shifting global energy dynamics, makes progress uncertain.

The danger is not that Namibia has no oil, but that it may never fully unlock it before the world moves on.

For a country that dared to dream of oil riches, the current pause is unsettling.

Big Oil are finding out that Namibia is not Guyana, and for a government and investors who hoped for rapid transformation, that reality is worrisome.