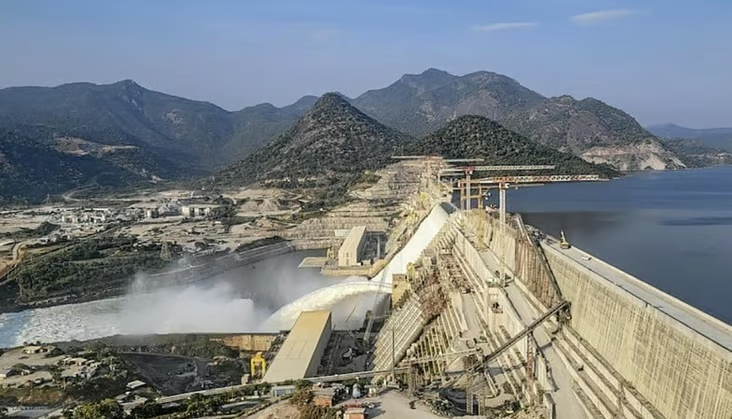

Ethiopia has officially launched the $5 billion Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Africa’s largest hydroelectric project, with a generating capacity of 5,150 megawatts.

The inauguration marks a historic milestone for Ethiopia’s energy ambitions, promising electricity access for millions and potential exports to neighboring countries.

However, the project continues to draw strong opposition from Egypt and Sudan over fears of water insecurity along the Nile.

Ethiopia describes the launch as a symbol of national pride and a catalyst for regional development while Egypt labels it as an existential threat and could endanger the country’s water supply, agriculture, and livelihoods.

In this article, Energy in Africa explores five critical reasons behind Egypt’s opposition to the mega project.

5. Water security at risk

Egypt is one of the driest countries on earth, depending on the Nile for nearly 90% of its fresh water, sustaining over 107 million people and irrigates farmland used for water-intensive crops such as cotton.

For Egypt, already classified as water scarce, GERD is seen not simply as a development challenge, but as a direct threat to national survival.

Cairo argues that any upstream disruption threatens this lifeline.

Officials warn that even a modest reduction of 2% in Nile flow could wipe out 200,000 acres of cultivated land, devastating food security.

4. No binding agreement

Another dispute stems from the absence of a binding deal on filling and operating the dam.

Ethiopia began building in 2011 and started filling the reservoir in 2020, despite objections from Egypt and Sudan.

Cairo insisted on a binding deal for filling and operating the dam.

Although Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan signed a 2015 Declaration of Principles requiring cooperation, Egypt says Ethiopia’s unilateral actions breach that agreement and international norms.

The Egyptian Foreign Ministry described Ethiopia’s unilateral moves “illegal” and harmful to downstream countries while Ethiopia insists on its sovereign right to resources.

3. Threat to livelihoods

In October 2024, the Egyptian Prime Minister, Mostafa Madbouly warned that prolonged droughts combined with unilateral operation of GERD could drive over 1.1 million people to lose their livelihoods.

The majority of Egypt’s workforce is tied to agriculture.

Reduced water flow could cripple rural communities, forcing mass displacement and increased socioeconomic strains.

Cairo argues that without safeguards, Ethiopia’s management of the dam could trigger a chain reaction of unemployment, poverty, and instability that extends beyond Egypt’s borders.

2. Loss of agricultural land

In addition, Egyptian authorities estimate that persistent disruptions could cause the disappearance of up to 15% of the country’s agricultural land.

The impact would be severe: reduced crop yields, rising food prices, and mounting pressure on an already stretched economy.

Officials have linked these risks to wider regional consequences.

Diminished farmland could accelerate internal migration from rural areas, strain urban infrastructure, and drive illegal migration across borders.

For a nation that imports much of its food and already struggles with inflation, the stakes are especially high.

1. Drought management concerns

Lastly, experts have warned that Ethiopia could choose to retain water in GERD’s reservoir to rebuild storage and maximise electricity production just when Egypt would most need the flow downstream.

A Nile researcher at the University of Toronto, Mohammed Basheer, for instance, , warns that the absence of a binding deal on the dam’s operations leaves Egypt vulnerable, especially in times of drought.

“There is no agreement on how GERD should be managed during and following periods of drought. Without an agreement, Ethiopia might adopt an approach that maximizes electricity generation following droughts, which would be unfavorable for Egypt.”

For Ethiopia, the GERD is a milestone designed to light homes, power industries, and drive national development.

For Egypt, it represents an existential risk to its water security, farmland, and millions of livelihoods.