Nigeria’s energy landscape is undergoing a profound shift. For decades, the country’s power narrative revolved around oil, gas, and subsidies.

Today, it is increasingly defined by solar panels, mini-grids, and international capital flowing into the renewable energy sector.

The change is being driven by three powerful forces. First, government reforms designed to attract clean investment.

Second, a consumer base desperate to escape unreliable and expensive grid power. Third, a surge of interest from multilateral lenders and multinational firms seeking growth in Africa’s largest economy.

Recent trade data show Nigeria has already overtaken South Africa as the continent’s largest solar importer.

At the same time, the Rural Electrification Agency (REA) is rolling out mini-grids across underserved communities, with backing from the World Bank and African Development Bank.

President Bola Tinubu has pledged to make Nigeria a renewable leader in Africa, and billions of dollars of foreign deals have been signed in the last two years.

The scale of demand is vast. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that more than 80 million Nigerians still lack reliable electricity access.

For investors, this represents not just a challenge but one of the most significant untapped renewable markets in the world.

In recent years, Nigeria has emerged as a testing ground for both large-scale solar farms and small pay-as-you-go systems designed to reach low-income households.

The question now is whether Nigeria’s renewable boom will translate into lasting development or remain another cycle of foreign-backed projects with limited local benefit.

New laws favouring transition

Nigeria’s renewable boom did not happen by chance. It is the product of shifting policies, international pressure, and domestic necessity.

The cornerstone of the initiative is the Energy Transition Plan (ETP), launched in 2022.

The plan commits Nigeria to achieving net zero emissions by 2060, aligning with global climate goals while signalling to investors that clean energy is now part of the country’s long-term strategy.

Policy instruments implemented included reduced import duties on solar panels and inverters, alongside expanded corporate tax incentives for renewable projects.

The Central Bank introduced green financing schemes, and development partners pledged billions in support.

According to a report by Bloomberg, these reforms were noticed by international financiers who had long viewed Nigeria as a risky market.

The government also launched a $10 billion transition fund in 2023.

Although disbursement has been slow, the announcement itself sent a clear signal to investors: Nigeria wanted to be a credible player in the global energy transition.

Another turning point was the removal of petrol subsidies in 2023. With fuel prices rising sharply, households and businesses looked for alternatives to diesel and petrol generators.

Analysts at the IEA noted that this policy shift created a “bottom-up” demand for solar and hybrid systems that complemented the government’s “top-down” transition agenda.

Yet challenges remain. Regulatory uncertainty continues to discourage some investors, and enforcement of existing laws can be inconsistent.

But the overall message is clear. Nigeria has begun to align its policies with the realities of a global shift away from fossil fuels, and investors are responding.

REA’s role in rural access

The REA has emerged as one of the most important players in Nigeria’s renewable story.

Tasked with expanding electricity access to rural and underserved communities, the agency has been at the centre of a quiet revolution in mini-grids and solar home systems.

By 2024, the REA had overseen the deployment of more than 1,000 mini-grids across Nigeria, with support from the World Bank, AfDB, and USAID.

Each mini-grid serves between a few hundred and a few thousand households, often replacing diesel generators as the primary power source.

Solar mini-grids in Katsina, for instance, have powered rice mills and processing plants run by women cooperatives, while in Niger State, farmers now use solar-powered irrigation pumps that cut costs and boost productivity.

In Plateau, small clinics operate refrigerators for vaccines for the first time, powered entirely by solar.

For investors, these projects provide a proof of concept.

They show that rural Nigerians are willing to pay for reliable electricity, even at higher rates than the grid.

A World Bank official told Reuters that “rural energy demand in Nigeria is underestimated. Payment rates are strong, and the willingness to invest in community schemes is higher than expected.”

Global firms have taken notice. Several European-backed developers, including firms from Germany and the Netherlands, are using Nigeria as their primary African market.

The off-grid sector now attracts as much international attention as the on-grid sector, with venture capital and development finance institutions playing a central role.

Still, scaling up remains a challenge.

Many projects rely on concessional finance, and questions persist about long-term sustainability. But the REA has shown that rural electrification is not just an aid project but a commercial opportunity, reshaping investor perceptions of Nigeria.

Multinational firms backing projects

Nigeria’s renewable boom is anchored by large international projects. Multinational companies, development banks, and private equity firms are pouring billions into solar, wind, and hybrid systems.

In 2024, Dubai-based investors announced a 1 gigawatt solar park in Kano, one of the largest single renewable projects in West Africa.

Siemens, already involved in Nigeria’s power sector reforms, is also piloting hybrid plants that combine gas and solar to provide reliable supply for industrial users.

Chinese companies dominate the supply chain. Panels, inverters, and batteries from China now fill warehouses in Lagos, Onitsha, and Kano. According to Al Jazeera, more than 70% of Nigeria’s solar imports come from China.

Western financiers are backing consumer-focused solutions.

Lumos Global, a Dutch-Israeli firm, serves more than 100,000 Nigerian households with pay-as-you-go solar kits that can be purchased via mobile money.

Shell-backed All On has invested more than $25 million in off-grid startups, while U.S. private equity firms have entered the mini-grid market.

Reuters estimated that renewable energy deals worth more than $2 billion were signed in Nigeria in 2023–2024, a figure that rivalled investment in oil projects for the first time in decades.

This international attention is not accidental.

Nigeria’s energy deficit is one of the largest in the world, and the combination of unmet demand, government incentives, and investor appetite has created a market that multinationals cannot ignore.

Presidential push for renewables

Political leadership also added weight to the momentum. At the 2024 COP summit, President Bola Tinubu pledged that Nigeria would lead Africa’s renewable transition.

His administration has directed ministries to prioritise renewable projects in new public-private partnerships, and incentives have been approved for foreign investors in the sector.

The presidency’s role is symbolic but significant. As the AfDB noted in a 2024 briefing, “Investors value political clarity. Even when implementation is slow, presidential endorsement lowers risk perception.”

Critics argue that Nigeria remains dependent on oil revenues, and gas is still central to industrial planning. But the public embrace of renewables by the president has shifted investor confidence.

The question is whether rhetoric will be matched by action. For now, investors appear willing to give Nigeria the benefit of the doubt.

Nigeria overtakes South Africa in solar imports

One of the most striking indicators of Nigeria’s renewable boom is trade data.

In August 2025, Nigeria overtook South Africa as the continent’s largest importer of solar panels and inverters.

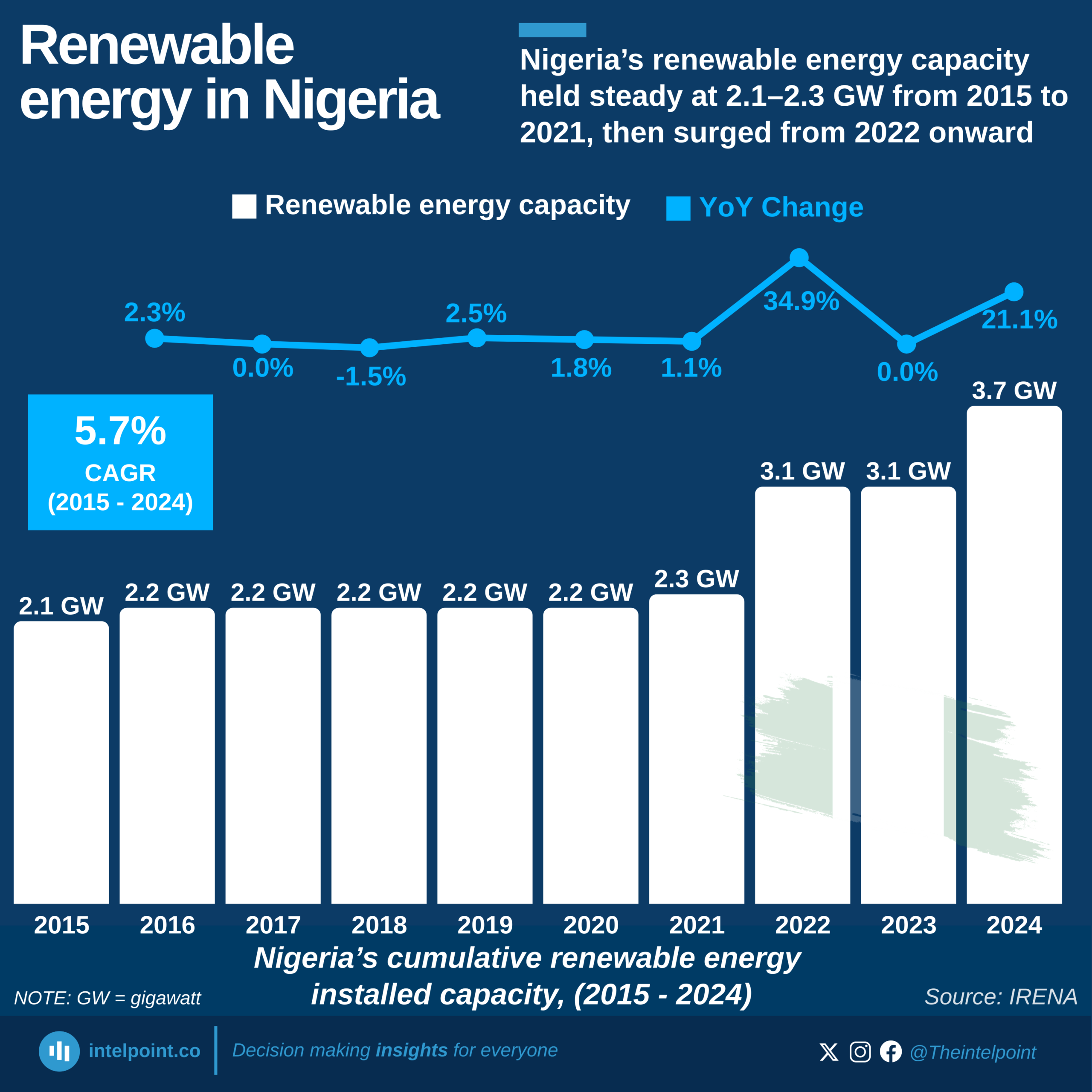

IRENA estimates that Nigeria added more than 1.2 gigawatts of distributed solar capacity between 2022 and 2024, far exceeding its progress over the previous decade.

This surge has created tens of thousands of jobs, from rooftop installers in Lagos to technicians maintaining mini-grids in Plateau.

The shift reflects Nigeria’s unique dynamics.

Unlike South Africa, where utility-scale renewable projects dominate, distributed systems have driven Nigeria’s growth. These range from rooftop solar in urban homes to mini-grids in rural communities.

But the boom comes with risks.

Foreign exchange shortages have pushed up the cost of imports. Local manufacturers struggle to compete with cheap Chinese products, and Nigeria risks becoming overly dependent on imported technology.

South Africa still leads in utility-scale renewables, but Nigeria’s rapid growth in distributed solar is changing the balance of influence on the continent.

For investors, this makes Nigeria a more attractive, albeit volatile, market.

Households and firms switch to renewables

At the consumer level, rising electricity tariffs and unreliable grid supply are pushing households and firms towards renewables.

Band A customers, who pay the highest rates, often face monthly bills above N80,000 for service that remains inconsistent. Frustrated by blackouts and estimated billing, many middle-class families are turning to solar not as a luxury but as a necessity.

Installers in Lagos told our reporter that demand for rooftop solar has doubled since 2024. “People want control,” one installer said. “They want certainty that when they switch on a light, it will stay on.”

Businesses are also defecting. Banks have announced plans to run clusters of branches entirely on solar, while shopping malls in Abuja now operate with hybrid systems. In Kano, a textile mill runs on a hybrid gas-solar plant financed by international lenders.

For investors, this creates a bankable market.

Households and industries with stable incomes are reliable customers for renewable developers. This dynamic is one reason why capital continues to flow into Nigeria’s sector, despite ongoing risks.

Experts urge caution

Meanwhile, analysts caution that the boom must be managed carefully. The IEA forecasts that Nigeria could become Africa’s largest renewable energy market by 2030, given its population and demand.

But there are warning signs.

Distribution companies warn that as wealthy customers leave the grid, their revenue base will shrink, worsening the financial crisis of the power sector.

Economists caution that without local manufacturing, most of the value will flow abroad. Environmentalists stress the need for storage and recycling systems.

“The opportunity is enormous, but the risks are just as real,” said a researcher at the Centre for Global Development. “Nigeria can attract billions, but if it does not ensure inclusivity, the transition will widen inequality rather than reduce it.”

Bolaji Moses, an investor in the solar panel business in Abuja, explained that the government is also a big player in the business.

According to him, the government has given a hidden contract to their friends, making it even harder for upcoming players to survive.

Our reporter was unable to confirm the claim made by Moses, as at the time of this report, his claim points to the lack of trust in government policy and the government at large.

The World Bank has emphasised the need for targeted subsidies for low-income households.

AfDB officials argue for building local supply chains. And IRENA notes that Africa as a whole must integrate renewable investments with industrial policy to avoid dependency.

Conclusion

Nigeria’s renewable boom is real, backed by billions in deals and growing consumer demand.

But whether this surge delivers broad development or reinforces existing divides will depend on choices made now.

If Nigeria can combine investor appetite with inclusive policies, the country could emerge as Africa’s renewable powerhouse.

If not, the boom may light up cities while leaving millions of rural homes in darkness.