South Africa remains one of the most coal-dependent countries in the world, with coal generating over 80% of its electricity.

The country is at a critical stage in its energy transition, struggling with its ambitious goal of phasing out coal by 2040 while ensuring energy security and economic stability.

The state-owned utility, Eskom, plans to transition to cleaner energy sources, targeting 32 gigawatts (GW) of renewable capacity by 2040, compared to its current 1 GW.

However, the road to decarbonization is far less smooth than policy papers suggest, with technical, financial, and socio-economic challenges to navigate.

Eskom’s ambitious roadmap

Eskom’s plan to transition to cleaner energy involves a dual approach, repowering aging coal plants with renewable or gas-fired technologies and developing new renewable energy projects.

The decommissioned Komati Power Station, closed in 2022, now serves as a pilot for integrating 150 MW of solar, 70 MW of wind, and 150 MW of battery storage, setting a good example.

The utility established an in-house renewable energy business unit to oversee these projects and foster private-sector partnerships.

This roadmap, aligned with global climate commitments, including the Paris Accord, is supported by a $2.2 billion funding commitment from World Bank-linked sources to fast-track the phase-out of coal.

The country’s goal is to repurpose aging coal plants into hybrid sites powered by solar, wind, and battery storage, with 5 GW of repowering projects already underway at six facilities.

In addition, the utility’s plan leverages the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Programme (REIPPP), which has driven private-sector investment in renewables.

By 2023, wind and solar contributed 4.5% and 8% of electricity generation, respectively, up from 0.4% each in 2014.

Despite this progress, coal’s dominance persists, and the transition requires a delicate balance to avoid disrupting energy supply.

Infrastructure and technical challenges

Meanwhile, South Africa’s aging grid poses significant technical challenges, hence the Integration of intermittent renewable sources like solar and wind.

Eskom indicated the need for 9,000 miles of new transmission lines over the next decade to accommodate large-scale renewable projects.

However, the current grid, designed for centralized coal plants, struggles to handle the decentralized and variable nature of renewables.

Thus, technical difficulties in stabilizing the grid could delay the 2040 target, as intermittent power sources require advanced energy storage and grid management systems.

Moreover, South Africa’s energy insecurity, marked by frequent load shedding, complicates the transition.

The coal fleet, with many plants exceeding their 40-year lifespan, operates below capacity, leading to power cuts of up to 12 hours daily in recent years.

To mitigate this, Eskom delayed the closure of three coal plants from 2027 to 2030, prioritizing energy reliability over rapid decarbonization.

This decision shows the tension between immediate energy needs and long-term climate goals.

The financial constraints

Apart from technical challenges, Eskom’s financial woes present a formidable barrier.

The utility’s financial woes began in 2006, when the company began dealing with growing revenue shortfalls, which have now accumulated to R535 billion ($30.6 billion), up from R1 billion ($57.2 million).

Eskom’s debt burden currently stands at R445 billion, with annual debt-servicing costs exceeding R40 billion ($2.3 billion), exacerbated by rising municipal arrears and regulated tariffs that fail to cover operational costs.

Thus, transitioning to renewables requires substantial investment, with estimates suggesting $136 billion is needed for new power generation capacity by 2040.

The Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), launched in 2021 with $8.5 billion in pledges from countries such as Germany, the UK, and the EU, aims to support South Africa’s decarbonization.

However, the withdrawal of $1.5 billion by the US in March 2025 has strained the initiative, although additional pledges from the Netherlands, Denmark, and others have raised the total to $11.8 billion.

Despite this, only $2.5 billion has been disbursed, indicating slow progress.

Renewable energy isn’t cheap, especially when it comes to national-scale projects.

South Africa’s fiscal constraints and limited access to international financing further complicate funding for renewable projects.

Socio-economic implications of the exit

Added the financial challenges, the coal sector employs nearly 90,000 people directly and supports millions indirectly, particularly in Mpumalanga, where 12 collieries operate.

The closure of five coal plants and 15 mines planned by 2030, followed by four plants and 23 mines by 2040, could impact 2.5 million livelihoods.

Workers in coal-dependent communities, like KwaGuqa in Emalahleni, express anxiety over job losses and inadequate retraining for renewable energy roles.

Eskom claims that the transition could create 300,000 jobs in the renewables value chain, potentially offsetting coal job losses.

While renewable energy can create new jobs in Mpumalanga, studies suggest that the transition from coal to renewables won’t fully offset the loss of coal-related jobs, necessitating economic diversification in agriculture, manufacturing, and tourism.

Political and industry resistance

Meanwhile, South Africa’s coal lobby, including major companies like Seriti Resources and the Minerals Council, has resisted rapid decarbonization, citing job losses and energy security concerns.

The Department of Mineral Resources and Energy historically prioritized coal, delaying policies like the Mine Closure Strategy and the Integrated Resource Plan, which hindered the transition.

Despite this, a 2024 court ruling declared plans for 1,500 MW of new coal power unconstitutional, reinforcing the shift toward renewables.

The government’s recent split of the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy into separate entities aims to reduce conflicts of interest and prioritize renewable energy development.

Opportunities for South Africa’s energy transition

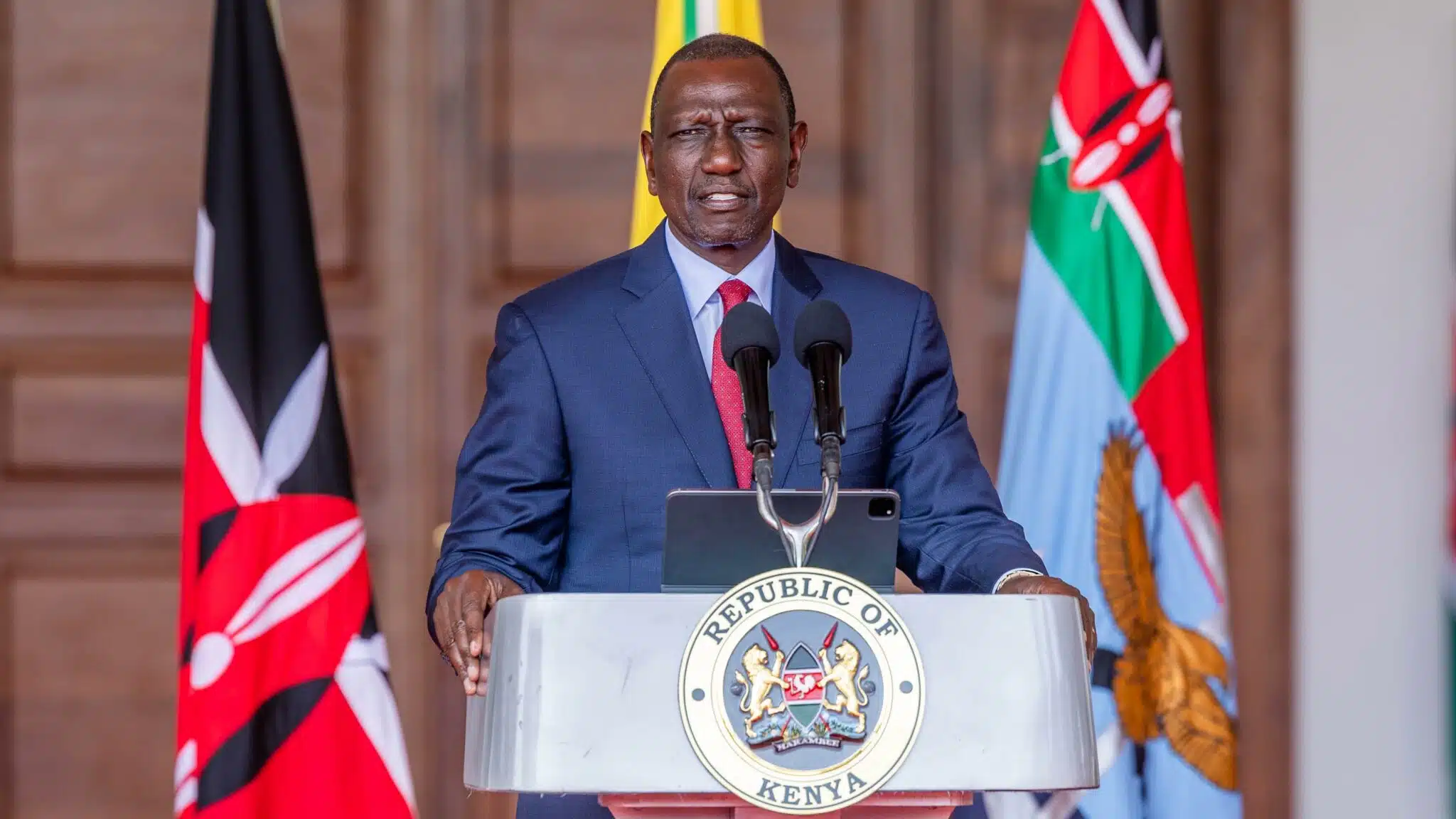

Moreover, a just transition, as outlined by President Cyril Ramaphosa in 2021, seeks to address inequalities, create jobs, and restore environmental systems law.

Initiatives like the Komati power station’s retraining center and land leasing for private renewable projects demonstrate progress.

The REIPPP has also attracted private investment, with solar capacity reaching 9 GW by 2025.

In addition, collaboration among government, labor, and communities is critical to align energy policies with socio-economic goals.