How long does it take to remove the heads of the two biggest energy regulators in Africa’s biggest oil producing nation? Probably two days of a smear campaign from a wealthy businessman. At least, that is what most Nigerians are finding out after the duo bosses of Nigeria’s upstream and downstream sectors tendered their resignation after meeting with President Bola Tinubu on Wednesday.

The events leading to their “resignation” could not have been more dramatic, with what seemed like a high cinematic twist following a thaw between billionaire Aliko Dangote and downstream chief Ahmed Farouk.

The brawl between both parties had been brewing for quite some time. And everyone who had been paying attention knew there were only one or two ways for it to end.

Aliko Dangote, Nigeria’s most popular entrepreneur and Africa’s richest man, is also the owner of the largest single train refinery in the world.

The refinery, built as a $20 billion wonder, can process 650,000 barrels of crude oil per day (bpd) at full capacity. It also hosts a complex petrochemical plant that produces fertiliser, urea, propylene and LPG. Dangote Refinery is the single biggest private investment in Nigeria’s economic history.

It also boasts of being the only functioning large scale refinery in the country.

So it is no doubt that such a mega project has far reaching consequences for the country’s economic future and even, as we are now finding out, its political direction.

All hell broke loose when the founder and president of the plant, Aliko Dangote himself, publicly accused the chairman of NMDPRA, Farouk Ahmed, of alleged corruption, including paying $5 million as his children’s school fees in Switzerland.

Dangote went on to say he would present evidence to anti graft agencies for Ahmed to be prosecuted.

“The Code of Conduct Bureau, or any other body deemed appropriate by the government, can investigate the matter.

“If he denies it, I will not only publish what he paid as tuition in those secondary schools, but I will also take legal steps to compel the schools to disclose the payments made by Farouk,” he said.

Twenty four hours after Dangote’s public outburst, both Farouk Ahmed and his counterpart in the upstream sector, Gbenga Komolafe, were shown the door.

How it all began

Ahmed had overseen the downstream regulatory body, where Dangote’s business operates, since 2021. His appointment followed the Petroleum Industry Act which allowed for the consolidation of both the midstream and downstream sectors.

Indeed, his relationship with Dangote had been a no love lost one since the latter began refining operations in 2023.

First, Dangote alleged that NMDPRA continued to issue importation licences discriminately to fuel importers, a move he believed would scuttle his refinery.

The refinery owner also pointed out that some imported fuel were substandard, dirty and cheaply dumped from countries like Russia and Malta, thereby distorting pricing.

In return, Ahmed, in what appeared to be his first public opposition against Dangote and perhaps his Achilles heel, said the refinery, then at an early stage of operations, was yet to produce industry standard fuel, citing higher sulphur content than required.

The tussle dragged on and eventually landed in court, with Dangote suing NMDPRA and fuel importers for N100 billion over alleged sabotage and indiscriminate issuance of licences.

NMDPRA fired back with a countersuit. The entire episode later ended in an out of court settlement, with Dangote withdrawing his case.

But none of these put the feud to rest. If anything, it intensified. Dangote repeatedly claimed NMDPRA’s actions threatened his refinery’s survival. On its part, the regulator quietly reminded him that he was not the only player under its watch.

No doubt, regulating Nigeria’s downstream sector is an exceptionally complex task. The Petroleum Industry Act of 2021 allowed for a free market system, accommodating importers and local refiners alike. At the same time, Dangote represents a major disruption to decades old downstream business practices. He also has everything to lose if the refinery fails, given the $20 billion risk, much of it from his personal pocket.

For a regulator, how do you balance market fairness with protecting local content? Ahmed failed that test, and the oil veteran paid the ultimate price.

The data that changed everything

The final straw was a fact sheet released by NMDPRA, which effectively indicted the refinery’s production capacity. The data showed that at no point had Dangote Refinery met 50% of Nigeria’s petrol consumption.

It was a bombshell.

Before the data release, Dangote had lobbied for a 15% import duty on petrol and diesel. The request was initially granted, only to be reversed by NMDPRA, clearly with federal backing, days later.

Dangote had also openly called for a total ban on petrol importation. With NMDPRA’s data showing the refinery has not been able to produce up to 50% of the local demands, his argument collapsed. If his demands had been granted, Nigeria would likely have faced shortages, panic buying and long queues nationwide.

One can only wonder whether the levy will now be reinstated with Farouk out of the way.

On Monday, Dangote escalated the fight, publishing details of Ahmed Farouk’s alleged corruption, including the names of his children and their school fees, in national dailies and online platforms under his name. It became a full blown dogfight, only this time between a billionaire and a regulator.

Dangote held nothing back. His media outreach amplified the allegations. Blogs, tabloids and online platforms ran the story. Ahmed’s reputation was dragged through the mud, and Dangote saw no reason to stop.

The last straw for the regulator

Perhaps the president, already under pressure for failing to protect Nigeria’s largest private investment, saw little reason to retain Ahmed. Politically, the easier decision was to remove the regulator.

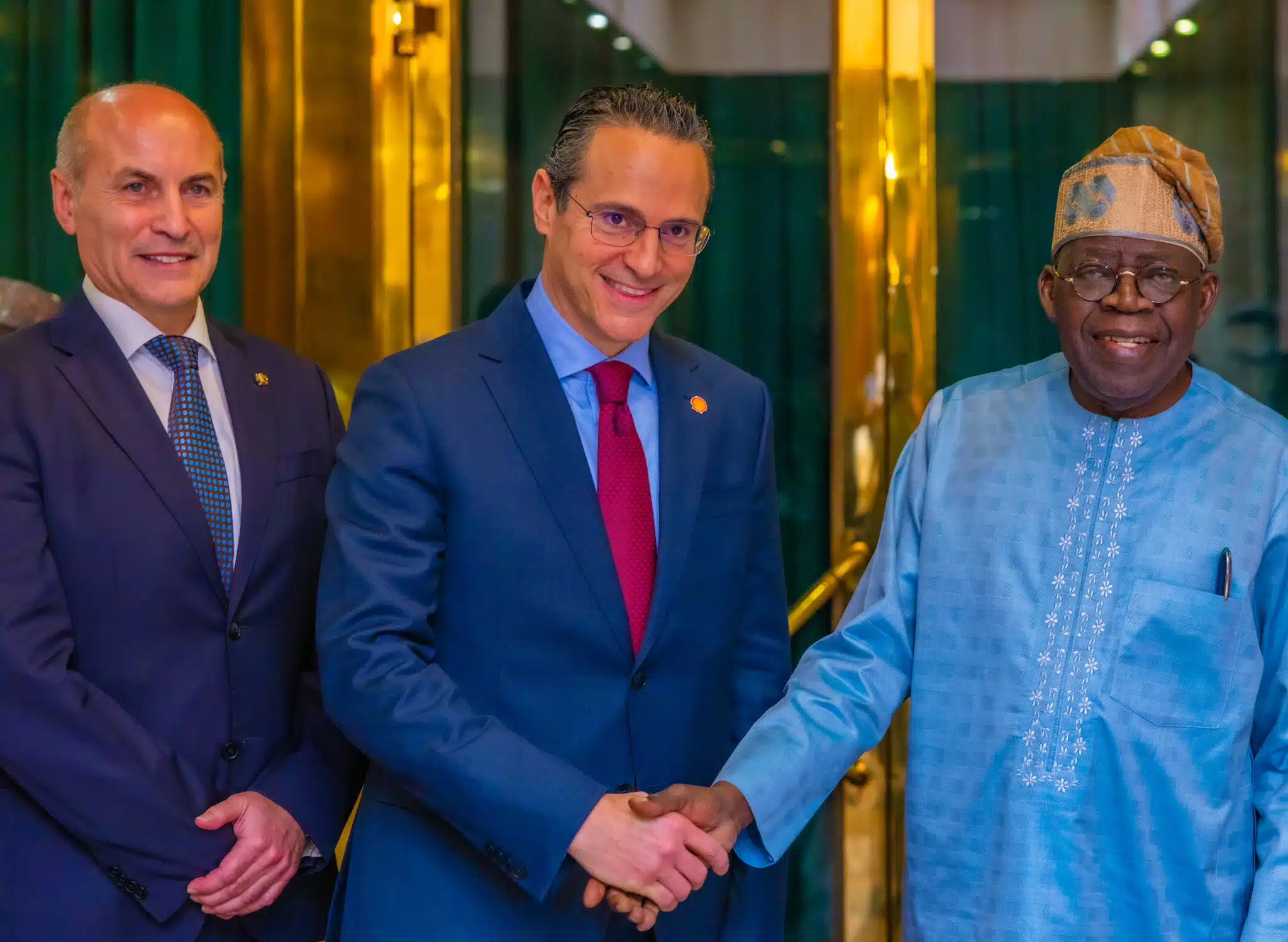

By Wednesday evening, headlines read: “NMDPRA boss Farouk Ahmed resigns after meeting with President Tinubu.” It was an obvious forced resignation. The government had effectively sided with the billionaire.

President Tinubu has since nominated Saidu Mohammed as Ahmed’s replacement.

That chapter is closed. Dangote returns to business, and the presidency regains some calm in the sector.

But for future regulators, the message is unmistakable. Going against Dangote comes at a cost. No one wants to be the next Farouk Ahmed.

Dangote has demonstrated that regulators can be toppled. Turn up the heat long enough, and the regulator is shown the door.

That is not a good precedent.